With the date for The Voice referendum approaching, I want to share some stories which I have been thinking and writing about for some time. They are not attempts to persuade anyone on how they should vote. They’re just my accounts of the indigenous kids I knew growing up and my experiences with indigenous folks through to the present.

My earliest memory of race was being picked up from school one afternoon. I was perhaps 6 or 7 at the time. At school I had picked up the children’s phrase “eeni meany myney mo, catch a nigger by the toe”. Upon reciting this with my younger brother in the back of the car, I vividly recall my Mum’s impassioned response from the front seat of the Commodore station wagon. It was said in a tone which was more than anger and I rarely heard, but I knew meant emotional and important: “don’t you ever say that word or boong, or black bastard do you understand me? I will wash your mouth out with soap if I ever hear you say that again”.

I grew up in the foothills of the Swan Valley in a place called Bassendean. Growing up in white Australia, you heard the racist jokes from a young age. An enduring memory I have is one day, my brother and I went to the local skatepark for the first time. It was adjacent to the public pool for children, which was funnily enough, funded by the patron saint of Bassendean in those days… the inimitable Rolf Harris.

It was after Christmas and all the kids there had new bikes and skateboards, with the gay ones on rollerblades (it’s a joke). Standing off to the side, I remember a young indigenous boy, who was perhaps 6 or 7. He was shirtless and standing there in his shorts with no shoes, looking on at things white kids had but he didn’t. He was asking other kids if he could have a go on their bikes, but was rebuffed every time. He just wanted to be apart of it and share in the fun, but for reasons he couldn’t yet conceive, he couldn’t.

As I was watching this an older boy rode up to me on his bike and said “don’t let the Abo’s ride on your bike; it’ll never come back”. He then told me a racist joke. I didn’t laugh, not only because I’d heard it before and it wasn’t funny, but because I was fixated on this young boy (not in the Rolf way) and the hurt I could see in him. It was like everyone knew why he didn’t have a bike except him.

During the course of my life, I’ve attended school with indigenous kids, been team mates, neighbours, colleagues and even been friends (full disclosure, I know one who hates me). As a criminal lawyer, I met and appeared for many indigenous clients. As a criminal, I have served a non-custodial sentence, and briefly been a co-tenant in a holding cell after chasing a “succulent Chinese meal”.

I’ve felt a comfort and affinity with indigenous people. Perhaps it’s my black armband view of history started by Mum’s moralising and all the time I spent riding the Midland train line. Maybe its my childhood socialisation, or perhaps, my Irish convict heritage has bestowed a subconscious solidarity that comes from having your ancestors raped and murdered by the English. Whatever it is, I have recently been bestowed the honour of being recognised as a “top fan” of the Facebook page ‘Noongars Be Like’.

Recently in Melbourne after a show, I was talking to a gentleman who confessed to having spent time in the West during “the great Perth shard boom of 2005-10. I lost four teeth, four months sleep and four months in Hakea (Prison).” But it was what he said next which kicked the filing cabinet of my memory.

“You know what I learned in Hakea? Is that I love the Noongars. They’re a bit like you and me bro. They’re funny and they have that rebellious fuck you spirit”.

I laughed, as my mind was instantly taken back to being 19 and having my first adult experience with the criminal justice system. I had been sentenced to a Community Service Order for an assault and other scallywag behaviour, the product of being overly refreshed.

Most days, I was one of the few white fellas (whadjelas) on the Corrective Services bus, but I didn’t mind it. The Noongar boys had me in fits of laughter all day long. I listened to their stories of offending, the hilarious tales of near misses, jackpots and moments of bad luck which led to getting caught by Police.

After a couple of days, I remember feeling a sense of envy at the instant camaraderie and kinship they had amongst each other. Even when they hadn’t met before, there was this seemingly instant bond and rapport they had with each other, one I’ve never seen or felt amongst my own kind.

On the bus, questions were asked about what you had done to get here. There was lots of stealing and other property offences. I was certainly not proud of what I had done to be there, but when it came my time to disclose, unlike the bike at the skatepark, not sharing wasn’t an option.

And so I began, trying not to sound proud of my conduct, but an element of me wanted to impress: “I had too much to drink at a uni party. I went into Hungry Jacks to get a burger to sober up. I broke the EFTPOS machine and when the big security guard put me in a headlock so I couldn’t leave, I used my guitar fingernails and eye gouged him. He let me go and I walked out into the arms of two detectives who’d stopped in for a burger.”

How they laughed. I was roasted in a way I have not been since. “Did you pull his hair too ya fucken girl!?”

I was sentenced to 60 hours of community service, but I didn’t serve the full 60 hours. On about the third day, one of the Noongar boys shared with me a loophole he’d discovered, namely “if you rock up on day when it’s pissing rain, they sign you off for a whole day bro.” I used this information to great effect and it was advice I passed on to my clients years later.

But back to Melbourne. After my friends comment, it reminded me of something I had noticed in that city; the notable absence of indigenous people. You cannot walk through the Perth CBD without encountering indigenous people, but in Naarm it’s the norm. In all the times I’ve been, the only indigenous people I crossed paths with, were down from Queensland, ironically to campaign against The Voice.

On my way home through the city, I encountered a moment of synchronicity. To my amusement, after thinking about the absence of indigenous people in that city, I crossed paths with an indigenous woman. We made eye contact. She smiled and pointed at me and said, “you look like Ben Cousins!” I laughed and stopped for a chat:

Me: “You’d be surprised how often I get that. What mob are you from madam?”

Lady: “Ahh. Not from around here. I’m a Noongar from Perth.”

Me: “Get the fuck out of here! I’m a Whadjela (white fella)!”

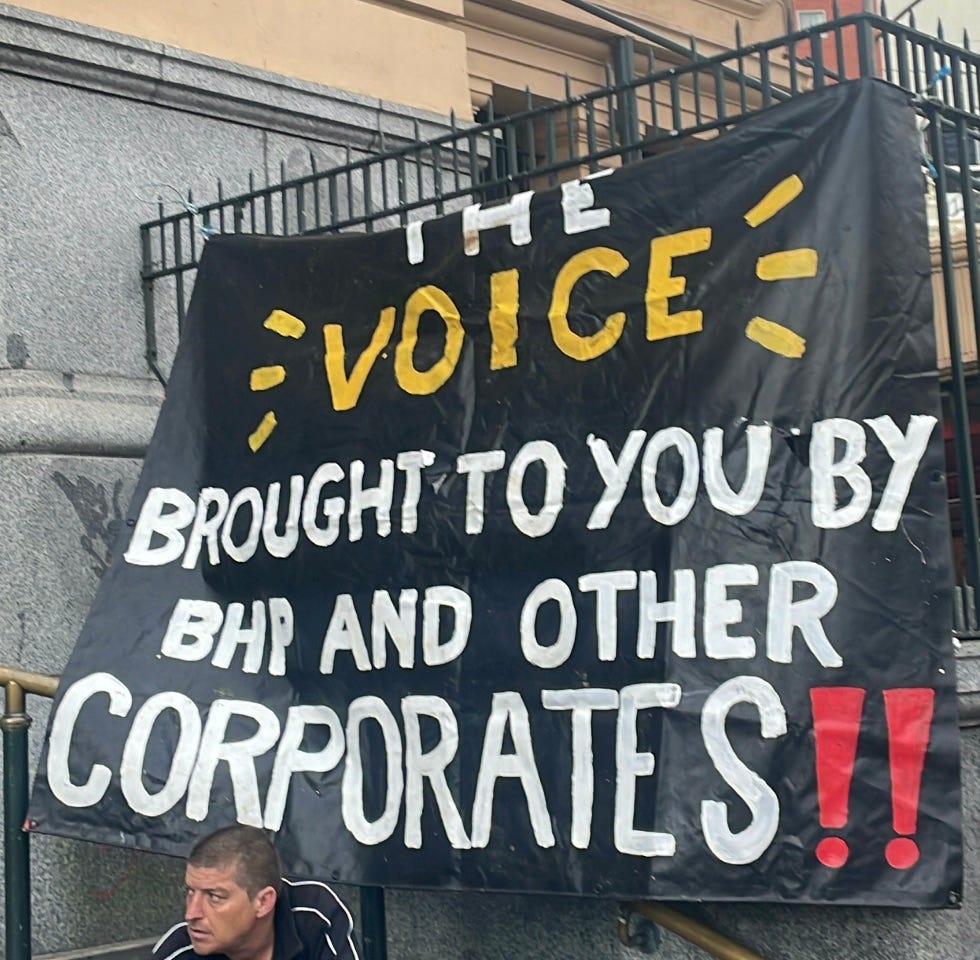

We laughed at this moment of small world synchronicity. Turns out she lives where I grew up in Bassendean. I asked her, “Can I ask, what do you think about the whole voice thing?” She replied, “I dunno. But if Rio Tinto wants it then I don’t think it’s any good for us”. I didn’t need Mark McGowan’s translator to understand her cynicism.

I laughed and wished her a good night. Riding the tram home, I was reflecting on the synchronicity when a memory popped into my head. It was of an indigenous boy I knew growing up. His name was Darryl.

Darryl was a Noongar boy two years my junior and my brother’s best friend in primary school. He was short, cheeky, charming, athletically gifted, with a rebellious fuck you spirit and quick wit. But he also had good manners, which endeared him to my Mum.

Like all people who naturally ooze charisma, he had a spark in his eye. He spent many weekends at our house and my brother spent some at his, but my Dad preferred Darryl stay at our house. For a time they were thick as thieves. The only time my brother got suspended at school, was after a teacher assaulted Darryl. Seeing this, my brother was incensed and promptly threw an object at the teachers head. In his mind, the rule of “keep hands, feet and objects to yourself” was redundant once a teacher did that, especially to one of your mates. Mum and Dad weren’t angry with him for it.

Darryl’s Mum and mine became friends. They would sit and chat on the verandah as their kids played. I remember his Mum as a strong and proud woman; however I must confess to finding her a little intimidating.

At school during recess and lunch, my friends and I would watch Darryl playing football. It was like watching a one man team. Watching him run around with the footy you couldn’t help but think, “he’ll play AFL for sure”. He had silky skills combined with hardness and flare. It was like watching a 40kg version of Byron Pickett, but what stood out more than anything, is he wasn’t scared. To me he appeared fearless, which was all the more impressive given he was a haemophiliac. Bruce MacAvaney would have had a wet dream commentating a game Darryl played. “DAZZLING DARRYL DELIVERRRRRRRRRRS”.

When disputes arose that morphed into school yard brawls, Darryl continued to be a one man team. I knew from his time at our house on the catch pads with my Dad, his pugilistic skills were excellent. Dad used to say “like a young Lionel Rose Daz!”. It was a great spectator sport to watch Darryl quite literally take on his whole class and drop kids twice his size, or to use his parlance “sit him on his hole”.

When I was about 12, I remember hearing a late night argument between my parents. Their marriage was on the rocks at the time, and I overheard a lot of arguments, most of which I don’t remember, but this one has stayed with me.

They were arguing about my brother and his friendship with Darryl. I recall hearing Dad say, “you know I really like Darryl and he’s a good kid, now. But as he gets older, he’ll start hanging around with his older cousins and I’m worried they’ll start stealing cars and breaking into houses and shit. I don’t want my son around that Jen”.

I have heard this referred to in Court by lawyers as a “negative peer association, which led to the offending behaviour”.

Mum replied indignantly, “that is such a racist thing to say Craig”. But it wasn’t the same tone I heard in the car as a younger child. There was an element of resignation in her voice. Whether the resignation was from a sense of knowing Dad’s mind wouldn’t change, or she couldn’t admit there was an unfortunate kernel of truth to his concern, I’ll never know. Maybe she’d just had enough of arguing with him.

About a year later, they separated. Dad moved out, my brother shifted schools and Darryl never came to our house again.

Fast forward about 20 years. It was about my second or third week practicing as a criminal lawyer in Perth. I was sitting in Court waiting for my matters to be called. In Court there is a hierarchy of seniority and so scum of the earth junior lawyers are made to wait their turn so as to know their place within the hierarchy.

It was the Committal Mention list in the Magistrates Court, which is the hearing before the indictable (serious) charges are referred up to the District Court for sentencing or trial. The video link list to Casuarina Prison was next and an older lawyer was at the lectern waiting for his matter to be called. The Orderly rose to her feet and said, “Calling the matter of Darryl S”.

I hadn’t heard that name in 20 years and I knew in my gut, it wasn’t a case of two Darryl’s with the same surname. The video link connected and I sat on the edge of my seat with my eyes glued to the screen.

The guard at Casuarina Prison greeted the Court. “Good morning Perth” he said. “Good morning Casuarina” the Orderly replied. “Could we have Darryl S please.” And then through the door he walked and appeared on the screen. “Is your name Darryl S?” the Magistrate asked. He answered with a despondent “yes”.

And there he was. The man I knew as a boy, sitting in maximum security wearing his prison greens. He was not yet 30, but he looked much older, his face bearing the scars of a life of disadvantage, delinquency and detention. Despite ageing, he still had a baby face but the spark in his eye I remember so well, was gone. He looked defeated, as if someone had taken the wind out of his sails, the jam out of his donut and the next 10 years of his life.

Then, like a rush of blood to the head, the memory of that boy playing on the oval, my brother’s friend who stayed at our house, his Mum on our verandah and that argument my parents had that night all came flooding back to me.

Was Dad’s concern for his son racist? Was Mum’s bleeding heart wrong? They were both coming from a place of sincerity, but if my brother and Darryl continued to be friends into adolescence, would my brother potentially be in the same place with him? Or if the doors of life had slid another way, with Darryl and my brother remaining friends, would Darryl’s life have gone in a more positive direction?

I sat and listened as I watched proceedings. He was already a sentenced prisoner for other matters and his remaining charges were committed to the District Court for sentencing. And like that, he was off the screen and back into the bowels of Casuarina Prison. His lawyer left the bar table and returned to the waiting table where I was seated to collect his briefcase. I asked him what Darryl was sentenced for, as I knew him growing up.

It was the proverbial shopping list of serious offences, the all too common product of methamphetamine addiction. Aggravated Armed Robbery. Assault. Reckless Driving to Escape Pursuit. Possession With Intent to Sell/Supply x2.

Darryl won’t be out of gaol before his 40th birthday. I wonder what he thinks about The Voice.